- Home

- Laura Brooke Robson

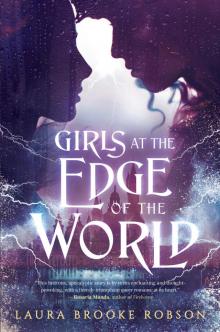

Girls at the Edge of the World Page 3

Girls at the Edge of the World Read online

Page 3

The name stuck. Katla calls herself a Brightwaller, but I hear it thrown around like an insult just as often. Most of the Brightwallers live outside of New Sundstad, in red-painted cottages in and beyond the boglands. Technically, it’s not illegal not to be part of the Sacred Breath, but it is illegal to be involved in any other religion. And since some Brightwallers still worship old spirits and sing hymns in ancient languages, they all get treated with suspicion.

I’m startled out of my thoughts when a hand, small and cold, snatches my wrist.

“Got you.”

My breath catches in my throat. Then I laugh.

I turn to see a waifish girl, too young for even the littlest troupes of flyers. She’s dressed in a big wool coat. She jangles a pouch of coins in front of my stomach.

“Why, you’re not a bog spirit,” I say.

She grins. “Pay up, ’less you saw me coming.”

“I did not,” I say. “You’re very sneaky.” I pat the sides of my costume for pockets that aren’t there. I turn to Katla. “Did you bring coins?”

She’s already handing one to the girl. “It’s like you didn’t even remember which festival this was.”

During the crane season festival, children slink around trying to frighten wealthy-looking Kostrovians. They’re meant to keep you on your toes, stop you from getting snatched by something really awful, like a bog spirit. Of course, most Kostrovians don’t really believe in bog spirits and their folkloric ilk. But it makes the children happy, and it makes me happy, and besides, all the spirit nonsense is just an excuse to give a hungry child a coin.

The girl vanishes in a current of bodies. The festivalgoers are winding away from the water.

“It’s not time for Nikolai’s speech, is it?” Katla cranes her neck.

“Let’s watch.”

The more I turn Gospodin’s words over in my head, the more I snag on what he said about Nikolai. I wish I could remember it exactly. Something about Nikolai and whether or not he knew about the flyers being kicked off the fleet.

I set off at a quick pace.

The crowd flocks to a pair of podiums surrounded on either side by dozens of flags and twice as many guards.

“A few people heckle Gospodin and he’s suddenly tripping over guards,” Katla says.

“A few might be an understatement.” I stand on my toes. “There are a lot of guards, though.”

At the seal season festival, a group of two dozen Brightwallers took advantage of the distraction and looted one of the grain stores full of fleet provisions. They left a message in Maapinnen, an old language Katla had to translate for me—sing as the sea. That’s become the rallying cry of the people, particularly Brightwallers, who don’t think they’ll be allowed on the fleet. The people trying to sabotage it. I’m not sure what the phrase means, but I guess the attack was enough to scare Nikolai and Gospodin. Today, the bloated force of guards scans the crowd with suspicion.

When Storm Ten hit, people demanded answers from Nikolai and Gospodin. Rumors spread that the royals were building a ship, and only a dozen of the city’s most important citizens would be allowed on board. We teetered perilously close to an uprising.

Then Gospodin and Nikolai told the city they would construct the biggest, most durable fleet money could buy. They’d fill the ships with food and drinking water to last the year of the Flood. And when the waters receded, whoever accompanied the royal fleet would have a hand in building the New World. Gospodin made it seem like any good citizens, any devout followers of the Sacred Breath, could be on the fleet. Anyone could dream of joining it. And others could stock their own ships. Assuming, of course, they had enough left over after the tithes to add anything to their personal stockpiles.

Now Kostrovians follow the Sacred Breath more diligently than ever. But there are still only three completed ships in the fleet, despite promises that more are being made. The country is pinched by rationing, especially after the locusts that followed Storm Seven and the devastating heat following Storm Six. It’s worse for families like Katla’s. She comes from a big family with plenty of mouths and not enough food. But, every month, a collector shows up to ask for rations: wood, coin, peat, water, flour. Everything the royal fleet needs. “A tithe for the common good,” Gospodin calls it, even though the good isn’t half as common as anyone might wish.

But still, everyone hopes. This was a lesson I learned quickly when the storms started coming. You think everyone will panic, but they don’t. They put their heads down, find new routines, and hope. It’s too hard to conceive that your life might be distilled down to a statistic: just one more dead body.

I thought I was too smart or too cynical to fall for it. But I hoped right along with them, thinking I’d be part of the royal fleet, thinking there was no way the flyers wouldn’t survive. I’m still falling for it, I realize. I’m still hoping.

The noise of the crowd around me fades. Nikolai and Gospodin climb the stage, Nikolai in black-and-gold regalia, Gospodin in white. If Gospodin is a pearly cloud, fair-haired and beaming, Nikolai is hidden in his shadow—his frown is as dark as his hair.

“He looks like he’s getting teeth pulled,” Katla says. “Not that I blame him. I’d probably look that way too if I spent all my time with Gospodin.”

“Katla!” I say. When I see her sly smile, I realize she’s just trying to provoke me. I bump my shoulder against hers. “Doesn’t Nikolai always look like he’s getting teeth pulled?”

“I’ve never understood why people think that whole brooding thing is attractive,” Katla says.

I glance at Nikolai again. The dark lashes; the geometric angles of his cheeks and jaw; the almost bored stillness to his face that disguises whatever he’s actually thinking. I can hear more than a few people whispering about him, our young and mysterious king. Katla might not get the brooding thing, but she might be the only one.

But it’s more than that. For me—for plenty of Kostrovians—Nikolai is a symbol of home. I’ve watched him grow up while I’ve been busy doing the same. He’s seventeen, same as me, and I first saw him up close when we were both nine. He was thin and brooding even then. As other royals die, fight, commit treason, abandon Kostrov, Nikolai has been a constant. What I feel when I think of Nikolai—this sense of place and home—is what I imagine the most devoted followers of the Sacred Breath feel when they think of Gospodin.

Gospodin leans against his podium and smiles broadly. The crowd angles forward to hear.

“Happy crane season,” he says.

The crowd erupts. Katla jabs my side with her elbow. She gives me a look that says I don’t approve of their unbridled love for this man, and I want to make sure you aren’t caught in the enthusiasm.

I shrug. I might not be a devout follower of the Sacred Breath, but I like Gospodin well enough. Unlike Nikolai’s stodgy councilors, Gospodin laughs warmly and often. While most men of his influence hide behind stone walls, Gospodin spends his time with the people, offering food and sermons.

I rise on my toes to get a better look. Nikolai’s eyes flit across the crowd, searching, and finally settle on me. My heart thumps. The weight of his gaze—like I’m an anchor in the chaos—settles on my shoulders. Nikolai allows himself the smallest smile—a twitch at the corner of his lips.

“To begin,” Gospodin says, “I want to share some good news. As you may have seen, the first three ships in the fleet are completed, and construction is well underway for the fourth. We’ve also secured a trade with Grunholt. Our peat for their lumber. Soon, we’ll have ten new ships to add to the royal fleet.”

An excited whisper ripples through the crowd.

“We are,” Gospodin says, “as always, servants of the people, and servants of the ocean. We will continue to build and acquire ships until every deserving Kostrovian has a place. And now, a moment of history.”

Gospodin launches into a wind

ing story about Antinous Kos, the father of the Sacred Breath, and his first year after the Flood, tenderly nurturing the wheat seedlings he brought from the old world. I think it’s supposed to be an allegory for patience. It’s not a virtue I possess, so I don’t listen too closely.

I scan the other figures near Nikolai and Gospodin at the podiums. When Nikolai announced his engagement to Princess Colette just before Storm Ten, I started seeing her violet-clad officials flanking Nikolai’s councilors. I don’t see any today.

I lean toward Katla. “Where are the Illasetish?”

Her eyebrows draw together.

When Nikolai finally begins to speak, I strain to hear. His voice is quieter than Gospodin’s. Steady, but quiet.

“After much discussion with my councilors,” he says, “I have called off my engagement to Colette, princess of Illaset.”

The crowd gasps. It’s all very dramatic. Gospodin’s lips twitch in a pleased little smile.

Nikolai shifts his weight. “We have decided the spots on the royal fleet would be better used to protect deserving Kostrovians, not the Illasetish.”

My heart leaps into my throat. When was this decided? What does it mean for the flyers?

“Captain’s Log teaches us that the earth will be unrecognizable after the Flood.” Nikolai glances at Gospodin. “Illaset has not prepared as well as Kostrov for the coming seasons. With their farmland disappearing, they have nothing to give us. If Illaset can’t offer weapons, or food, or ships, the union isn’t a favorable one. We wish the best of luck to our Illasetish friends in the face of the coming storms.” He takes a deep breath. “As such, Mariner Gospodin and I have decided that instead of Princess Colette, a Kostrovian girl will be the next queen.”

The crowd starts to buzz, and Gospodin looks more pleased than ever.

Gospodin offers us a winning smile. “Nikolai will make his decision in three months’ time, on his eighteenth birthday, after the bear season festival. Think of your own sister, your own daughter, wearing the queen’s crown. She’ll be the mother of the New World. She could be among us today.”

Katla scoffs loudly. A few festivalgoers shoot her dirty looks. To me, she says, “They’re just trying to distract us from the storms.”

“I don’t know,” I say. “It sounds like something out of Tamm’s Fables. Like ‘The Girl Who Married the Whale King’?”

“Yes, well, Nikolai is a human and not a whale, and I don’t imagine he’s going to marry a girl in a dress sewn by sand eels.”

Gospodin caps off the occasion with a triumphant declaration that we Kostrovians are terrifically brave, and thanks to our enduring belief in the Sacred Breath, we are all quite safe indeed. When the crowd finally starts to disperse, it’s time to warm up for our performance.

“He’s so smug,” Katla says.

“Seas, Katla, be quiet. He’s just doing his job.”

She shrugs.

“Let’s get to the stage,” I say. “Before Adelaida starts yelling for us.”

I turn too fast. My arm jostles a shoulder. I spot the girl I’ve hit for just a moment. The moment lasts long enough for me to meet her eyes, to see the high bridges of her cheekbones, her olive-toned skin, and the dark curls spilling out of her hood.

She tilts her head at me, as if we know each other, but—I think I would recognize her, if I’d seen her before. I open my mouth.

Then I hear a murmuring. It’s not the girl. She looks up too, her chin high, eyes searching.

Katla grabs my wrist. “Hear that? We have to go.”

The murmurs are coalescing into words. All at once, I make it out: Sing as the sea.

A clump of mud—or a peat brick, maybe—whizzes through the air. It comes from somewhere so nearby that I duck, cover my head with my arms.

More mud. Raining around us. All of it directed toward the podiums, toward—

Nikolai and Gospodin are covered in it. Huge brown splotches stain Gospodin’s perfect white uniform. The guards swarm in front of them, holding up their hands, but the mud-throwers stop as quickly as they started.

Katla pulls my wrist hard. “Come on.”

Between the shoulders of two guards, Gospodin’s eyes find me. My breath catches. His gaze narrows. Head tilts to the side.

I try to shake my head, try to look bewildered. I didn’t throw any mud.

Katla finally manages to tug me away. I remember the girl with the cloak, but she’s already gone. We reach the edge of the chaotic crowd, squeezing through to where the street widens out again.

Katla curses under her breath.

Did Gospodin think I had something to do with that? I’ve lived in the palace half my life. I might not be diligent about attending Sacred Breath services, but I’m loyal to the crown. I press a hand to my cheek and find it mud-splattered.

“What was that about?” I say.

“More of the peat harvesters got arrested last week for skimping on their tithes,” Katla says, her voice low. “I guess they’re trying to make a statement.”

“Well, maybe if everyone stopped sabotaging Gospodin and Nikolai, the tithes would ease up. The fleet’s supposed to have room for all of us.”

Katla lets out a disbelieving laugh. “Even with ten ships from Grunholt, you expect half a million Kostrovians to fit on fourteen ships?”

I look down. “No.”

“Come on,” she says. “Adelaida really will be yelling for us now.”

I feel foolish. “Right behind you.”

4

ELLA

I decide I like the tall red-haired flyer, even though she jostles me in the crowd. Her resting face is a scowl, which I heartily approve of. But when Nikolai announces his marriage scheme, her attention sharpens. Maybe I shouldn’t like her after all.

Then people start throwing mud. It suits Nikolai, being covered in mud. He should wear it always.

I turn and squeeze back through the throng as fast as I can. I’m planning enough illegal activities. I’m not about to get arrested for a crime I didn’t commit.

It’s crowded in Kostrov. Too crowded. We went to plenty of festivals when I was a child, but none made me feel so claustrophobic. Not just because there are so many people. It’s because of the way Nikolai and Gospodin talk. They make me feel slimy. Lied to.

Did I ever hear a speech like that at a Terrazzan festival? I don’t think so. I can’t remember ever seeing the Terrazzan Righteous Mariner in person, but then again, I’m not sure I could even pick him out of a crowd.

My family went to Sacred Breath services once in a while, but our farm was a two-hour walk from town. My parents were stoic, dutiful types. They planted and hoed and baked and cleaned, and I never heard them complain. But when it came to Sacred Breath services, they always had an excuse not to go. I thought it was because they didn’t like being inside, didn’t like staying still, didn’t like trying to corral my uncorralable brothers.

It didn’t occur to me that I might be the reason they weren’t going until I was fourteen. I found them murmuring over mugs of spiced cider in the kitchen, their heads bent, hair mingling. When they noticed me, my mother looked angry and my father looked sad.

“What?” I said.

Neither of my parents was much for wasting time.

“Brigida Barbosa,” my mother said. “The girl who sells flowers on the corner of Vine and Main.”

I tensed.

“Apparently,” my father said, “she was caught with a girl traveling through from Cordova. They were both branded as sirens.”

My stomach went tight. “Branded?”

“As a warning,” my mother said. Her cheeks were flushed. I could see, then, that she was gripping the edge of the counter, and even that wasn’t enough to keep the tremble out of her shoulders. “To men.”

My father covered her hand with his. They both looked at

me for a long moment. None of us said anything. Not about sirens. Not about Brigida Barbosa, who always gave me a daffodil, no charge, when we walked down Vine Street. Not about the way I tucked the bloom in my hair and kept it there until it wilted. We all just looked at each other.

We never went to another Sacred Breath service.

Maret catches me as I reach the fringe of the crowd and pulls me to an alley between a cobbler and a postal office. There’s a poster advertising their need for fit young men for postal runner job—no insolence. Kostrovians only.

“What are you doing?” Maret’s cheeks are flushed pink.

“Well,” I say, “currently, I’m wondering why delivering mail is too difficult a task with which to trust my countrymen.”

“What? You know what, never mind. I meant at the speech.”

“I wanted to watch.”

“That’s not what I’m talking about,” Maret says. “I saw you slinking toward the Royal Flyers. You nearly knocked one down.”

“I would never slink.”

I did slink toward the flyers, of course. I’ve spent enough time training to be one of them that I was curious. Besides. I liked the scowl.

Maret lets out an exasperated breath. She pats her head and tucks a loose curl back under her hat. I wonder if being unobtrusive is hard for her. She’s just so glamorous. Cassia once told me that before Maret’s exile, she had a closet of dresses in every color I could imagine. When I said I could imagine earwax yellow, Cassia assured me Maret had such a gown, with snot-green satin heels to match.

I, on the other hand, am dressed in a formless black cloak disguising a formless black dress, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. The cloak covers the siren tattoo on my wrist, and I can’t ask for more than that.

“The mud,” I say. “Did that ever happen to you?”

“Of course not,” Maret says. “The people loved my father. They loved me. Though I can’t say I’m surprised this is what people think of the crown now that Nikolai’s in charge.” She makes a sour face. “And all that about the fleet. Big enough for every deserving Kostrovian? I don’t believe it. Nikolai and Gospodin have no idea what they’re doing.” She glances around the alley, like she might’ve spoken too loudly, but it’s just us and the smell of dead fish.

Girls at the Edge of the World

Girls at the Edge of the World